Leah Phillips was born and raised in Louisville, Kentucky, the nation’s largest producer of tobacco; and also a state where lung cancer is the leading cause of death. Leah knew all this, but she didn’t smoke and wasn’t notably spending time in environments with second-hand smoke. She was rigorous about maintaining her health. When she got a persistent cough at age 43 (in 2019) it took a long time — about four months and a lot of run-arounds — before she received a diagnosis of stage 4 EGFR-positive lung cancer, a lung cancer that is common among nonsmokers. Even in a state where lung cancer is so prevalent, they almost didn’t catch it with Leah.

In January 2024, Leah began making videos on TikTok — a little cautiously at first, then with growing insistence and bravery — about a disease burdened by misunderstanding and moral judgment. Today, she has nearly twenty thousand followers; and she includes dozens of other voices in the account to share their stories. She’s quick to note that there’s no moral superiority to young lung cancer that happens without smoking; but she wants to disseminate the message that you can still get lung cancer, even if you don’t smoke. Leah’s early motivation with these videos — to make this different type of lung cancer visible, to give people information and tools for protecting their health, and to provide a measure of hope as someone living through this diagnosis — became the three main principles of the Young Lung Cancer Initiative, a nonprofit she co-founded with Bianca Bye in 2024 to advocate for people with lung cancer under 50.

In their mission to expand the idea of who might get lung cancer, and to empower those who do have lung cancer, the Young Lung Cancer Initiative offers webinars about treatment. They also want to help in immediate ways: like by giving gift certificates to people in treatment or travel grants of $500 to put toward some “leisurely travel” to give people with lung cancer a bit of a rest.

In her conversation with Jadey, Leah talks about survivor’s guilt, about rerouting shame, the stigma of lung cancer, and the therapeutic power of advocating for other people. Advocacy, for her, is about learning how to insist on care.

Leah speaking about lung cancer.

Q:

You’ve been very intentional about using social media as a tool for education and connection. Why was that approach important to you?

A:

We’re approaching this work in a very different way through social media. We make short, digestible pieces of information people can actually consume. Someone can watch while they’re sitting in the carpool line, while their child is napping, or in a dentist’s waiting room. Even though it’s the Young Lung Cancer Initiative, everything we share is information that can benefit people of any age.

I also know how desperate people are for connection when they’re sick. And I want to educate not just patients, but the world at large: you can get lung cancer even if you’re young, even if you’ve never smoked, even if you’re healthy. As a former educator — I taught high school before staying home with my kids — this feels like an extension of that work. It’s emotionally exhausting, and sometimes physically and mentally exhausting too. But I remember how desperate I was for someone like me to say, ‘Hey, come sit with me, here’s something that can help.’

Out in the big world of lung cancer, it seems to be divided between smokers and non-smokers. It shouldn’t be divided at all. We all have lung cancer. We’re all fighting for research, funding, and education. Nobody deserves cancer.

Q:

What does self-advocacy mean for lung cancer patients in practical terms?

A:

You know your body better than anyone. If something doesn’t feel right or isn’t working, you have to insist on care. We have patients who go a year without a diagnosis, going back to the doctor again and again trying to figure out what’s wrong. I believe oncologists go into this work with good intentions. But people have to be persistent.

No one cares about your health or your life more than you do, and that’s incredibly hard when you feel awful and overwhelmed. Time is of the essence with lung cancer. Biomarker testing is critical — no matter your age — because treatments can be completely different depending on those results.

Out in the big world of lung cancer, it seems to be divided between smokers and non-smokers. It shouldn’t be divided at all. We all have lung cancer. We’re all fighting for research, funding, and education. Nobody deserves cancer.

Leah Phillips with Dr. Singhi, her thoracic oncologist, at World Conference on Lung Cancer.

Q:

Can you walk us through the early symptoms that led to your diagnosis?

A:

It started as a dry cough. I went to the doctor within a couple of weeks and said, “I have this cough, but I feel fine otherwise.” They told me it was likely post-viral and prescribed steroids. Of course, I felt better for a bit. But then my primary care doctor went on leave, and I kept going back to the practice, probably every two weeks from September through December, because I wasn’t getting better.

The cough worsened to the point where I couldn’t sleep. In hindsight, I was losing weight, but I was running, the kids were going back to school — it all felt explainable at the time. I wasn’t putting the pieces together.

My husband had been diagnosed with prostate cancer at 42, about 18 months earlier, and we learned he has the BRCA mutation. So cancer was already part of our lives.

When I was finally diagnosed, a doctor told me, ‘Our goal is to keep you here until Christmas next year. You probably have six to twelve months. You should go home and get your affairs in order.’ Then he left the room. I was 43. My kids were 14, 13, and 9. I was hysterical.

Right around then, I went for a run — if you can even call it that. I think I was trying to prove to myself and my kids that everything was okay. I was diagnosed on December 18, discharged on the 22nd, and by the 26th I was at the gym. We weren’t okay. We weren’t normal. But I was trying to make it look that way.

Leah in treatment.

Q:

You live in Kentucky, which has one of the highest rates of lung cancer in the country. Does that affect how you navigate your advocacy?

A:

It definitely makes things trickier. There’s also so much misinformation. Kentucky is actually number one in the nation for early detection screenings, which is great — but you have to be over 50 and have a smoking history to qualify. People like me don’t even meet the criteria. I’m not “better” because I didn’t smoke; it’s just different. I was younger, I had no known risk factors, and that meant I wasn’t eligible for screening — so I was diagnosed at a late stage.

Q:

You’ve spoken openly about the shame you felt after your diagnosis. How did you shift that?

A:

I heard my husband on the phone tell someone, and I looked at him and said, ‘Don’t you ever tell anyone I have lung cancer.’ I knew exactly what people would think: that I was uneducated, that I’d smoked since I was ten, that I’d spent my life in tanning beds, that I had bleached blonde hair and missing teeth. That stigma was ingrained in me growing up here. It came from those commercials, the ones where people are holding their trachs.

It was embarrassing, even though there was no reason to be embarrassed. I didn’t want my kids to have to defend me. And they did have to. People asked them, ‘Why did your mom smoke? That was dumb.’ And then I had a child crying because her mom never smoked. But even if I had — so what? Smoking is an addiction. Many people start when their brains aren’t fully developed. What 50-year-old says, ‘I think I’ll pick up cigarettes today’? Judging people for decisions they made when they were young — and are now addicted to, and struggling to quit — is wrong. Alcohol kills people too, but no one shames you for opening a bottle of wine.

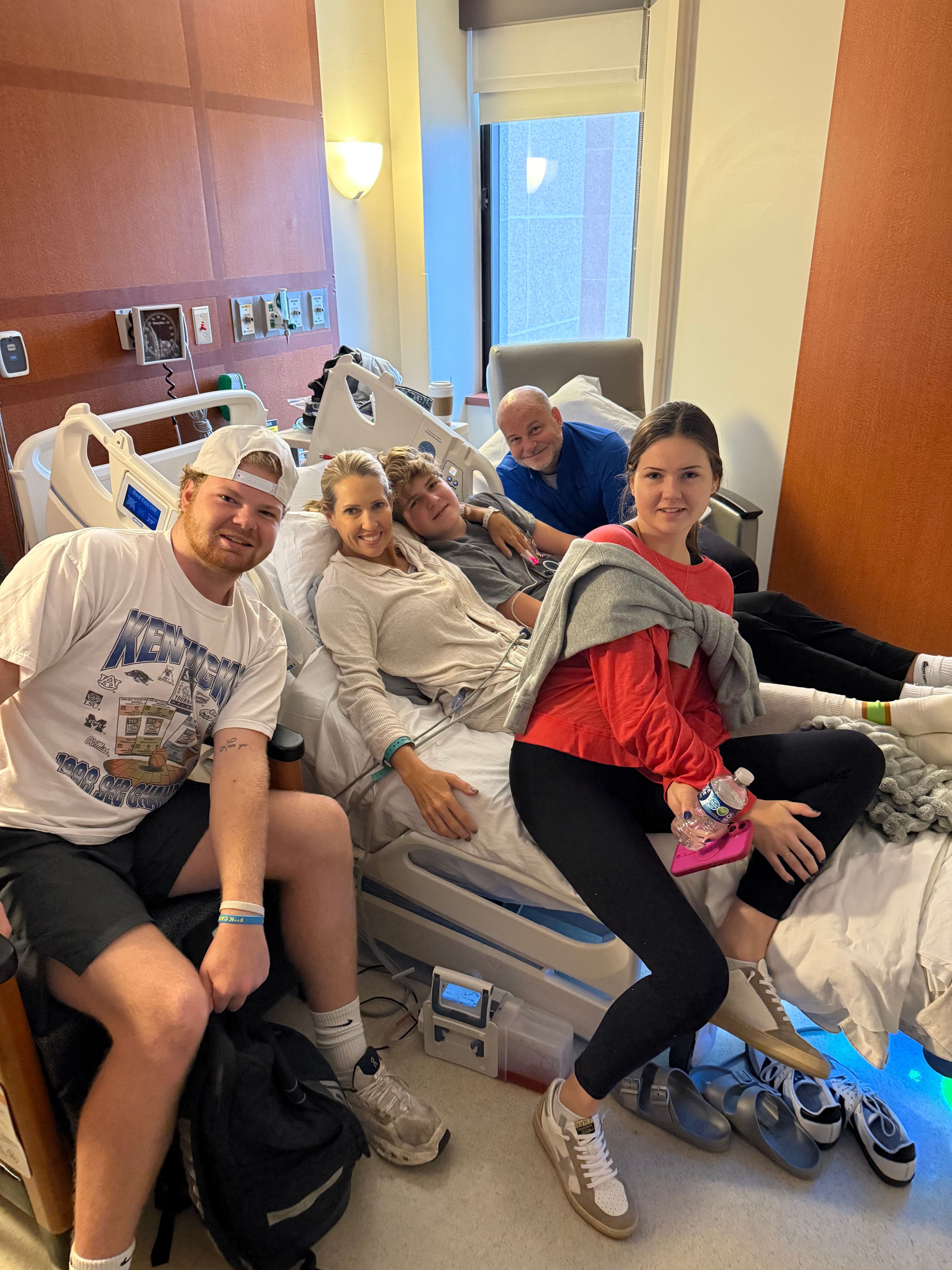

Leah with her family at the hospital.

Q:

Survivor’s guilt is something you’ve spoken about often. How do you navigate that?

A:

I became close friends with a woman who was thirteen years younger than me. She had stage 4 lung cancer too and lived about 15 minutes away. She had just had a baby; she was six months postpartum when she was diagnosed. She had symptoms during pregnancy. She passed away within two years. The morning after she died, her husband called me at six a.m. and told me she was gone. I was crushed. That’s when the survivor’s guilt started. I kept thinking, Why me? Why am I still here?

The statistics said only five percent of stage 4 patients live five years. After months of deep depression, I told my husband, ‘Someone has to make up that five percent. I’m going to be one of them.’ I thought when I hit five years I’d want a big celebration — but I didn’t want to talk about it at all. How do you celebrate without hurting the people who aren’t here, or who may never get there?

I’ve seen a therapist every two weeks since my diagnosis. We talk a lot about survivor’s guilt — about holding the truth that others would give anything to be in my shoes. But I have to think about what I've done for the community at large, and that the positive things that we've done outweigh my feelings of survivor's guilt.